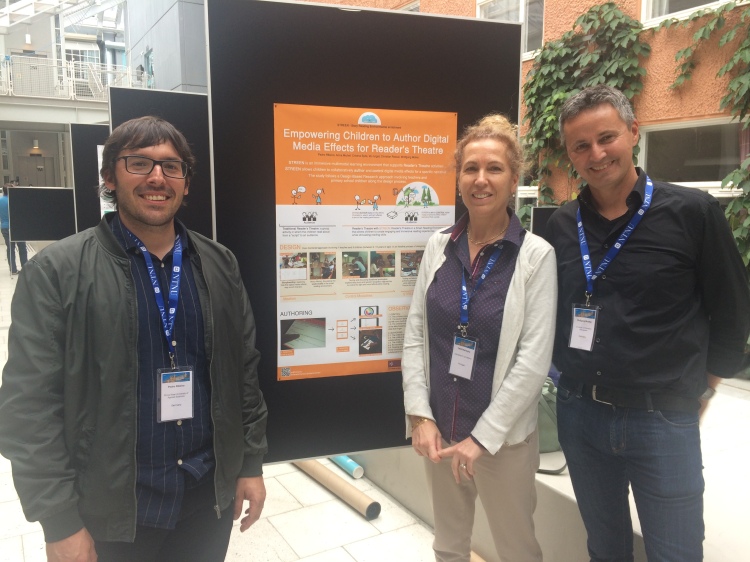

Preschoolers’ Agency in Technology Supported Language Learning Activities

Nathaly Gonzalez-Acevedo, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain

That technology is part of very young children’s lives is not new, however, how they interact with it is still an area that is under exploration. In this line, research is interested in how children make sense of technology and how the interaction between very young children and technology is orchestrated.

In a recent Short-Term Scientific Mission in Helsinki, in collaboration with the University of Helsinki and the Playful Learning Center, the interaction of very young children with technology was explored as a multimodal interaction. The aim was to explore preschoolers’ agency during technology supported activities, in a specific sociocultural mediated and located context, and explore similitudes and differences in different sociocultural contexts in order to discuss and gain deeper insights in how agency is enacted by preschoolers and how, if so, different sociocultural contexts frame preschoolers’ digitally mediated agency.

It was observed that the materialization of agency is shaped by the context and thus the experience has highlighted how in the context analyzed children are encouraged to be themselves in front of the adult as a way to acknowledge power relation in classrooms which differs from my own research in which in order to recognize the power relation and its influences the child is given space without the adult in autonomous and collaborative tasks.

In a brief, but relevant observation to a classroom, in a school near Helsinki, an episode that represents how children can approach and interact with technology, in the context observed, took place serving this short post as an illustration of a multimodal interaction between very young children and technology.

The Classroom

The classroom was set to play in different corners, one corner being the use of the tablet. The teacher had a register of all the children that had played with the app to make sure that all children had, at some point, gone through that corner and played with the app aimed at working the reading of time in clock. The child, a 5 year old, was given the app Moji Clock and was given instructions on how to play by the adult setting the corner. The adult spent the time the child needed to understand the task and left him with headphones to play on his own.

Episode 1

The child was playing with the app and a second child comes and asks “How it works that game”. That simple question makes evident that the second child understands many of the affordances of the tablet and the use of apps. The child knows it is a game and that he is aware that it is not an open answer game, by asking how it works and looking at the screen the child recognizes that there are rules to be followed in the game. It is interesting, as well, that he uses the word game and not activity or any other synonym. That choice of vocabulary shows that the child uses the word used to describe those apps; “games”. In this short interaction a great understanding, for a very young child, of the use of technology can be appreciated.

Episode 2

In another episode, during the same activity, the child with the tablet who is wearing headphones, starts putting them on and taking them off as if playing with his acquired capability of listening to the app’s audio, and the key to the game, or the rest of the class. He is playful, and being observed by the researcher, a new adult for him, he acts very comfortable playing with this selection of what to listen to. This seems a multimodal choice, what background information do I need or want and the ability to choose and act on it. This highlights that a child can use his agency to explore the affordances of the technology and use it according to his needs.

Episode 3

During the same observation, the child who is aware that the researcher was observing him during his play with the tablet, decided to make explicit his actions on the tablet. The act of making explicit his thinking started when the learner found a more complex stage of the game. The monologue went like this

-yeah, yeah three o’clock, what?

-What?

-What?

-Half past eight

-It going to be so hard, look (to the second child)

Picture 1: App: Moji Clock (screen capture), 8:30

Picture 1: App: Moji Clock (screen capture), 8:30

The clear difficulty being the use of half past. It is interesting how the child verbalizes this difficulty by asking a question that seems reflective as he is all the time looking intensely at the screen. In a second part, however, the child who is visibly thinking about the time uses the help of the second child

- I don’t know how to make half past four

- Here (another child)

- I don’t know it is here or here (pointing at 3:30 and then 4:30)

Picture 2: App: Moji Clock (screen capture), 4:30

This short episode shows how a very young child is able to reflect on what he is doing while playing so displaying the ability to reflect on the content he is working and not only oriented to the technology. In the same line, the child shows how he is able to verbalize the problem he is facing and sharing his ideas with the second child so allowing space for collaboration in a technology supported activity.

This last episode points out that very young learners can be able to make explicit and talk about the process of facing a difficulty in an activity supported by technology as well as sharing ideas with peers in order to solve, in this case, content problems.

This informal observation in a friendly environment allows some key points to be made. Very young learners can be able to explore the affordances of technology, can be able to use some related vocabulary and show understanding of its meaning (what is a game and what are its characteristics, for instance) and can be able to make visible their thinking and ask for a peer’s collaboration. This does not mean that all children will reproduce these skills, but it is clear that very young children can be able to, given the right stimulus, make a sensible and adequate use of technology in a school setting like the one presented.

It also highlights that a child’s agency in, technology-supported activities, in the light of the observations made, per se can be similar in different contexts. The data analyzed in my research points at very similar enactments of agency. However, there are differences in how the adult shapes the structures in order to promote agency. It would be interesting to explore this point further.

Picture 1: App: Moji Clock (screen capture), 8:30

Picture 1: App: Moji Clock (screen capture), 8:30